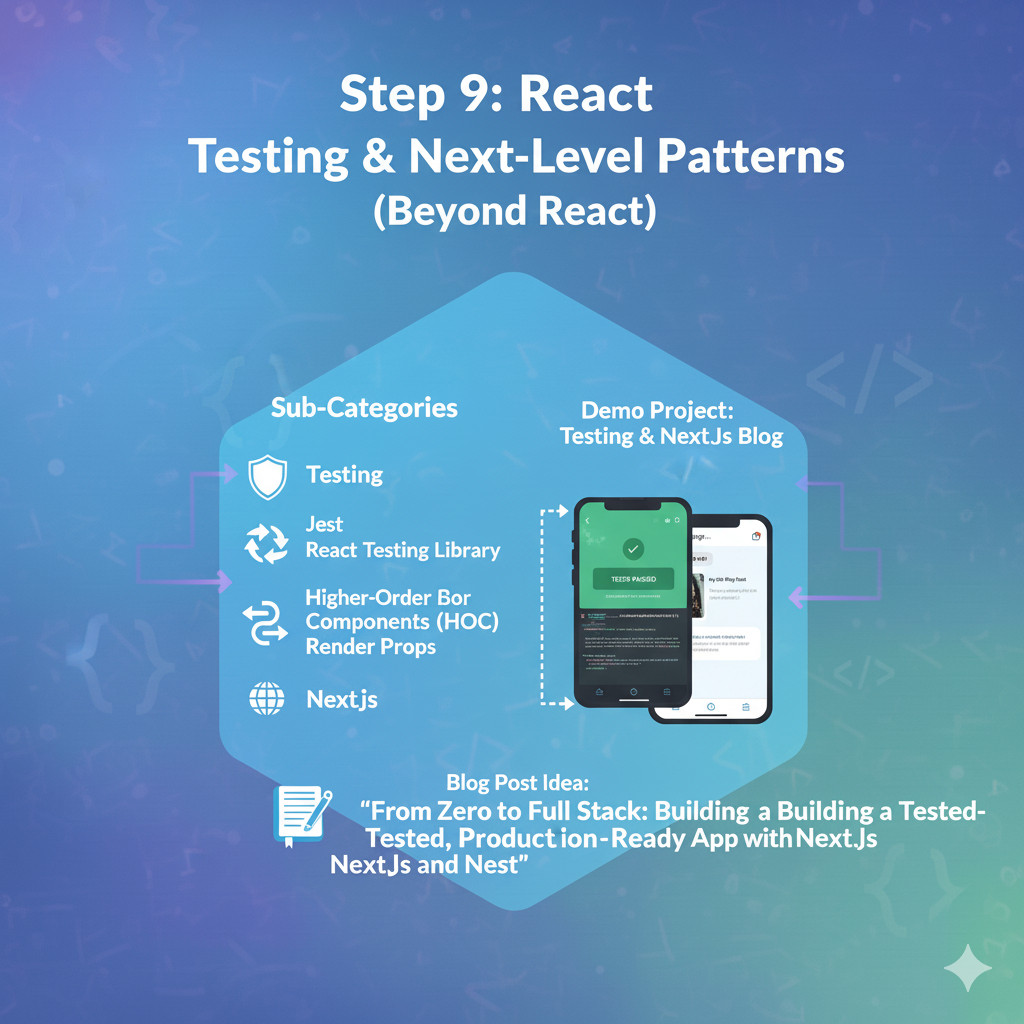

1. 🧪 Testing with Jest & React Testing Library

This is the most critical professional skill on the list. Writing tests ensures you can add features or refactor code without accidentally breaking something else.

The Philosophy: “Test your code like a real user would use it.”

a) The Tools

- Jest: This is your “Test Runner.” It’s a framework (often built into new projects) that provides the tools to find test files, run them, and report

PASSorFAIL. It gives you functions liketest()andexpect(). - React Testing Library (RTL): This is the key. It’s a library for “rendering” your components in a virtual test environment and interacting with them.

The Core Idea (Don’t Test Implementation Details):

- BAD ❌: “Test if the

Countercomponent’scountstate is1.” (This is an implementation detail. What if you renamecounttovalue? The test breaks, but the app still works.) - GOOD ✅: “Test if the user sees ‘0’ on the screen. Then, find the button with the text ‘Increment’ and click it. Now, test if the user sees ‘1’ on the screen.” (This tests the user experience, which is what matters.)

b) Coding Steps: Testing Your “Counter” App (from Step 2)

Let’s write a real test for the counter you already built.

Step 1: Setup If you used create-vite-app, you’ll need to install and configure Jest/RTL. (This is a blog post in itself!). For now, let’s focus on writing the test.

Step 2: Create a Test File If your component is src/App.jsx, you create a file named src/App.test.jsx. Jest will find it automatically.

Step 3: Write the Test This code follows the “Arrange, Act, Assert” pattern.

JavaScript

// src/App.test.jsx

import { render, screen, fireEvent } from '@testing-library/react';

import App from './App'; // Your Counter component

// The test() function from Jest

test('Counter should increment when the button is clicked', () => {

// 1. ARRANGE: Render the component

render(<App />);

// 2. ASSERT (Initial State): Check if '0' is on the screen.

// 'screen.getByText' is from RTL. It searches the rendered HTML

// for text. This will fail if '0' isn't there.

expect(screen.getByText('0')).toBeInTheDocument();

// 3. ACT: Find the "Increment" button and click it.

// 'fireEvent' is from RTL. It simulates user events.

fireEvent.click(

screen.getByRole('button', { name: /increment/i })

);

// 4. ASSERT (Final State): Check if '1' is on the screen.

// We expect the '0' to be gone.

expect(screen.queryByText('0')).not.toBeInTheDocument();

// We expect '1' to be present.

expect(screen.getByText('1')).toBeInTheDocument();

});

When you run your tests (e.g., npm test), Jest will run this, and you’ll get a green “PASS.” You’ve just built a safety net for your code.

Your Blog Post Idea: “Why I Was Scared of Testing (and How React Testing Library Made It Easy)”

2. 🏛️ Advanced Patterns: HOCs & Render Props

Before Hooks (Step 6) simplified everything, how did people share stateful logic? They used these two patterns.

You don’t need to write these, but you must understand them to read older React codebases (which is 90% of all React code).

a) Higher-Order Component (HOC)

A HOC is a function that takes a component and returns a new component with extra logic or props.

Example: A withAuth HOC that checks if a user is logged in before rendering a component.

JavaScript

// 1. The HOC (a function)

function withAuth(WrappedComponent) {

// 2. It returns a new component

return function(props) {

const { user } = useAuth(); // Some hook to get the user

if (!user) {

return <LoginPage />;

}

// 3. It returns the original component, passing in the user

return <WrappedComponent {...props} user={user} />;

}

}

// 4. How you use it

const MyProfilePage = (props) => <div>Hello, {props.user.name}</div>;

export default withAuth(MyProfilePage); // Wrap it!

Problem: “Wrapper Hell.” You’d see components wrapped 5-6 times.

b) Render Props

A component that takes a function as a prop (usually called render) and calls that function with its internal state.

Example: A <MousePosition> component that tracks mouse state.

JavaScript

// 1. The component with the logic

class MousePosition extends React.Component {

state = { x: 0, y: 0 };

handleMouseMove = (event) => {

this.setState({ x: event.clientX, y: event.clientY });

};

render() {

// 2. It calls its 'render' prop with its state

return (

<div onMouseMove={this.handleMouseMove}>

{this.props.render(this.state)}

</div>

);

}

}

// 3. How you use it

<MousePosition

render={mouse => (

<h1>The mouse is at {mouse.x}, {mouse.y}</h1>

)}

/>

The “Aha!” Moment: A Custom Hook (like useAuth() or useMousePosition()) replaces both of these patterns. It’s the modern, clean way to share stateful logic.

Your Blog Post Idea: “How React Hooks Replaced HOCs and Render Props (A History Lesson)”

3. 🚀 Next-Level: Server-Side Rendering (SSR) with Next.js

This is the most important “next step” in the entire ecosystem.

The Problem with Your Current React App (a “Client-Side” SPA):

- Bad SEO: When Google’s bot visits your site, it gets a blank HTML file. The content (

<h1>Hello</h1>) only appears after the huge JavaScript file downloads and runs. - Slow Initial Load: Users (especially on mobile) stare at a white screen while that JavaScript downloads.

The Solution: Next.js (A React Framework) Next.js solves this by pre-rendering your pages on a server.

- Static Site Generation (SSG): (For your blog) At “build time,” Next.js runs React, fetches your posts, and generates static HTML files (

/posts/1.html,/posts/2.html). When a user visits, they get a fully-formed, instant-loading HTML page. This is the best of all worlds. - Server-Side Rendering (SSR): (For dynamic pages) When a user requests a page, a server runs React on-the-fly, generates the HTML, and sends it. It’s a bit slower than SSG but perfect for pages that must be fresh (like a user’s dashboard).

Demo Project: Re-build Your Blog (from Step 5) with Next.js

- Start a new project:

npx create-next-app@latest - File-Based Routing: Forget

react-router-dom. To create a page, you just make a file.src/pages/index.jsx-> becomesyoursite.com/src/pages/about.jsx-> becomesyoursite.com/about

- Dynamic Routes:

src/pages/posts/[id].jsx-> becomesyoursite.com/posts/1,yoursite.com/posts/2, etc.

- Data Fetching (SSG): Inside your page file (e.g.,

[id].jsx), you export a special function calledgetStaticProps.

JavaScript

// src/pages/posts/[id].jsx

import { getPostData } from '../../lib/posts'; // A helper function you write

// 1. Your React Component

export default function PostPage({ post }) {

// 3. The 'post' prop is passed in by Next.js

return (

<div>

<h1>{post.title}</h1>

<p>{post.date}</p>

<div dangerouslySetInnerHTML={{ __html: post.contentHtml }} />

</div>

);

}

// 2. This function runs at BUILD TIME on the SERVER

export async function getStaticProps({ params }) {

// 'params.id' will be the 'id' from the URL

const post = await getPostData(params.id);

return {

props: {

post // This 'post' object is passed to your component

}

};

}

You’ve now built a blog that is blazing fast, perfect for SEO, and uses the most in-demand skill in the React ecosystem.